VITALINA NO LABIRINTO DA SODADE

Vitalina Varela is a film of ghosts and shadows, memory and dreamlike visions, wanderings and distant voices. As in the previous Cavalo Dinheiro, darkness is the centre of gravity of a slender and monolithic story, forged by the drifts of the past. Like Ventura also Vitalina moves inside paintings (sometimes baroque, sometimes expressionist) crossed by light, the only life-giving element of a tragic past. Another exploration of solitary and interconnected spaces, as claudicating as the existences of those who inhabit them, yet so resistant. An epic of everyday life, realistic and symbolic - and dazzling and spiritual -, pure in the presences of those who continuously walk through it experiencing oblivion, constantly waiting for revelation (the cinema?). Costa creates timeless figures capable of crossing continents and epochs, condensing presences of history and guardians of another truth. Cinema as a space of vital claim and resistance of identity, material and terribly physical in the depths of shadows that appear as black holes and colours so bright that they seem to be in relief. And right at the end, that darkness that seemed to trap everything, every ray of light in its essence, disappears leaving room for the day. As if it was still possible to look for an innocence or a miracle of the image that can recover a lost time, through the hyper-realism of bodies and places that live the essence of a lost and distant duration. Vitalina remains, with her abstract and inscrutable charm, on her shoulders the weight of what has been, in her eyes the horizon of a future never so uncertain. What we see is only a fragment of the present, torn from abandonment, from the mourning of a (perhaps) not entirely irreversible despair.

One of the first feelings we had when we saw Vitalina Varela is that your cinema never ends, it is endless. You don't like the word "end", that’s why we believe that you have always made the same film. We want to give, from the beginning, a positive connotation to this statement. For us you have remained faithful to your cinema, to your idea of cinema. We see the same modesty in filming, the same cinematic coherence and radicality. Leaving a character in front of a camera, so that he can reflect everything, feelings, tremors, vibrations confirms that for you filming is a very physical act and cinema is a moral issue.

One of the first feelings we had when we saw Vitalina Varela is that your cinema never ends, it is endless. You don't like the word "end", that’s why we believe that you have always made the same film. We want to give, from the beginning, a positive connotation to this statement. For us you have remained faithful to your cinema, to your idea of cinema. We see the same modesty in filming, the same cinematic coherence and radicality. Leaving a character in front of a camera, so that he can reflect everything, feelings, tremors, vibrations confirms that for you filming is a very physical act and cinema is a moral issue.

Yes, definitely... from the first minute of my first film. Today, I've certainly gained more experience. Right from the start, I would say from my fourth feature film, I was able to obtain the conditions of production, of practical organisation of my films, as I wanted. My work today is much closer to the production aspects than to the more properly directed ones. I have no hesitation in saying that perhaps, because of the way I set up my work, I am closer to the figure of the producer than the director. This forces me to make an effort, as you say, much more physical, or practical, and less intellectual. I think this is a good thing. I am closer to reality and the production aspects. On the other hand, since 1995/1997, I am very attached to some people, to Cape Verdean emigrants, to the spaces where they lived and that they had to abandon today, to the ghosts of those places, to their new houses. I don't know whether to define this aspect as moral, ethical or... there's a word I like very much: decency, it's like in Italian. Maintaining a certain decency to make decent films in these rather indecent times in which we live. Especially with cinema, where money circulate easily and you can spend without limits. Today I am even more attached to these people and their stories, so it is even more important to behave decently. It is also necessary to have a certain attitude when filming, both when approaching these people and when visiting their places. You can't make fun of them. I make films that are more concrete, practical, close to the ground, to be always up to these people and their stories.

Thirty years have passed since O Sangue, and before that since your lessons with António Reis. How do you think your gaze have changed? And how the world you look at?

I don't think much has changed, maybe the passing of time has tempered my gaze, some impulses. I'll never forget the first concepts Reis put forward in his lessons. He told us that it was important, when you start thinking about making a film, to start from something real, a face, a place, rather than a story. He proclaimed: "Look at the stone, the story will come later, and if there is no story, it doesn't matter” He taught us how important it was to see and listen. When I entered the School of Cinema, I was convinced that cinema had to have limits, I wasn't attracted to special effects, but I had an inclination for violent things. And Reis agreed with me. He loved the mixture of violence and tenderness and they are always present in his lessons and in his cinema. António was like that, he had a very hard side, like the landscapes and the people he filmed, and at the same time he had a great tenderness. A strong fragility and a soft, tender violence. He was affectionate and violent, he was rough in his manifestations, because he was an extremely direct person. Perhaps these characteristics of his accompanied me and were tempered by the passage of time. I am still referring to the people of Cape Verde, the people I elected as protagonists and heroes of my films. I tried to use myself to follow the feelings of these people, and perhaps through them... In other words, my gaze is strongly connected to their. My gaze on everything: on reality, on the world. I agree with their point of view, I feel very close to them. For example, with Vitalina there is a great closeness and sharing. I wanted the film to be for her, to walk alongside her and the people I film: Ventura, Vanda, Vitalina and all the others. I wanted it to be a collective film, so to speak, that it wasn't my gaze that prevailed, but that it was made through the eyes and bodies of these people.

Vitalina and Ventura, two stories, two points of view to look at history. Are they complementary? What is their relationship in your path of rewriting history?

I'm not saying it was fortuitous, or by chance, but the encounter between Vitalina and Ventura in this film is very interesting. It gives voice to their gaze, doesn't it? It represents an opportunity, that of having at the same time, and perhaps for the first time, the male and female gaze on the theme of immigration, or migration, of human displacement, no? On the fragility of these communities, not only in the Portuguese suburbs, but of the entire planet. I managed to unite the two points of view, which are complementary, but also conflicting. The abandoned, or forgotten, Cape Verdean woman I am filming for the first time has Ventura as a counterpoint, which I have filmed before. Ventura is the man who doesn't remember and that's why, for forgetting her, he ends up getting a little lost. Evidently, for me, there is something in cinema that has a lot to do with history, the one with a capital letter, or perhaps more with justice. History and justice are relatively linked. Cinema has something to do with that. For me, it has always been a means of opposing, or questioning, certain stories that have been badly told by History. The women's stories, for example, of these women, have been improperly told, as have the stories of these pioneers, these emigrants. I think that one of my films, as well as other contemporary filmmakers, comes to mind Wang Bing, for example, perhaps managed to turn, to put back in the right place, some stories that have been badly told by many other films, by many other books, by many television reports, etc.. It is necessary to carry out this operation. Perhaps it's a somewhat polemical and provocative statement, but we have to abandon the documentary. We mustn't rely too much on the urgency of a documentary style or attitude, do you understand? I don't think this is what we need, so-called documentary clarity or precision. I think we need to think more about fiction, reflection. Fiction can bring deeper aspects, fallen into oblivion, buried, to the essence of things. This is what we need. With Vitalina Varela, for example, I almost wanted to bury the documentary (laughs), everything related to the documentary, under the word of Vitalina, which is a very strong word, very violent, very collective almost. At a certain point Vitalina reaches an almost mythical state, in my opinion, she talks about a very ancient past, as if she were the first woman, the first abandoned woman. Last week she gave an interview to a Portuguese newspaper and expressed a very beautiful concept: "This film is for all women who suffer". She composed a sort of pamphlet about the condition of all women who suffer. It’s as if Vitalina was at the origin of everything, like the "zero point", the first cry. Perhaps the political aspect of this film consists precisely in the attempt to bring Vitalina and her words forward - without separating her from the social context, which is well present in the film - through her interpretation, her acting. To succeed in making all this a political act, do you understand?

I'm not saying it was fortuitous, or by chance, but the encounter between Vitalina and Ventura in this film is very interesting. It gives voice to their gaze, doesn't it? It represents an opportunity, that of having at the same time, and perhaps for the first time, the male and female gaze on the theme of immigration, or migration, of human displacement, no? On the fragility of these communities, not only in the Portuguese suburbs, but of the entire planet. I managed to unite the two points of view, which are complementary, but also conflicting. The abandoned, or forgotten, Cape Verdean woman I am filming for the first time has Ventura as a counterpoint, which I have filmed before. Ventura is the man who doesn't remember and that's why, for forgetting her, he ends up getting a little lost. Evidently, for me, there is something in cinema that has a lot to do with history, the one with a capital letter, or perhaps more with justice. History and justice are relatively linked. Cinema has something to do with that. For me, it has always been a means of opposing, or questioning, certain stories that have been badly told by History. The women's stories, for example, of these women, have been improperly told, as have the stories of these pioneers, these emigrants. I think that one of my films, as well as other contemporary filmmakers, comes to mind Wang Bing, for example, perhaps managed to turn, to put back in the right place, some stories that have been badly told by many other films, by many other books, by many television reports, etc.. It is necessary to carry out this operation. Perhaps it's a somewhat polemical and provocative statement, but we have to abandon the documentary. We mustn't rely too much on the urgency of a documentary style or attitude, do you understand? I don't think this is what we need, so-called documentary clarity or precision. I think we need to think more about fiction, reflection. Fiction can bring deeper aspects, fallen into oblivion, buried, to the essence of things. This is what we need. With Vitalina Varela, for example, I almost wanted to bury the documentary (laughs), everything related to the documentary, under the word of Vitalina, which is a very strong word, very violent, very collective almost. At a certain point Vitalina reaches an almost mythical state, in my opinion, she talks about a very ancient past, as if she were the first woman, the first abandoned woman. Last week she gave an interview to a Portuguese newspaper and expressed a very beautiful concept: "This film is for all women who suffer". She composed a sort of pamphlet about the condition of all women who suffer. It’s as if Vitalina was at the origin of everything, like the "zero point", the first cry. Perhaps the political aspect of this film consists precisely in the attempt to bring Vitalina and her words forward - without separating her from the social context, which is well present in the film - through her interpretation, her acting. To succeed in making all this a political act, do you understand?

Yes, it is very clear this aspect... If we remember correctly, Vitalina is the first character who arrives from Cape Verde to Lisbon. We met the other characters already living in Lisbon. Vitalina, therefore, reverses a trajectory. For the first time someone comes from Cape Verde and has the opportunity to see life in the big city. Vitalina has waited a lifetime to make this journey, but she will discover that Lisbon, for the Cape Verdeans, is nothing more than a hostile space, the space of exclusion and disintegration. Lisbon is a prison for the Cape Verdeans, just as Tarrafal was for the Portuguese.

Yes, that’s right, very well said. The hospital you see in Casa de lava, where Leão, the Cape Verdean construction worker who works in Lisbon, is being taken, and where he is in a coma following an accident, was actually the infirmary of the Tarrafal concentration camp. At the time I was accused of having treated those places a little frivolously (laughs), of not having filmed them in a respectful way. I took a somewhat polemical attitude at the time, but that was what I felt, that’s what I still feel. The neighbourhood of Fontaínhas, which I met before it was demolished, where I filmed, always seemed to me a fortress, a labyrinth erected by emigrants, not just Cape Verdeans, in an attempt to protect themselves from the city, from the famous white city. You’re right, that’s exactly what it is. Something happens with the arrival of Vitalina in Lisbon. She is not only a concrete woman, very physical, carnal, even full of desire... Vitalina would have liked to see her husband, her body. She says so in the film, and that means she is a very carnal woman, but at the same time there is a side into her which seems to be a kind of what was called the Visitation in painting. It is the Visitation of someone who comes from elsewhere, who brings news from another country, from another time. Vitalina is also a ghost. Her arrival disturbs and disrupts the lives of the inhabitants of this neighborhood. It raises a kind of scandal. It confronts them with certain truths. She manages to line up against a wall these Cape Verdean men she calls lazy, immemorial, alienated. She lines them up like a policeman in front of suspects (laughs). She qualifies them, she points them out, she tells them facts, I don't say crimes, but almost... While I was conceiving the film I remembered to include Ventura and for him I thought of the figure of the priest. Ventura needed a sort of counterbalance. I thought it was interesting the contact between this woman, this force of the past that represents Vitalina, and this judge of the present who has literally lost his mind. Just as she has lost her faith, her faith and her head. I thought, once again, that cinema is probably made for this... It’s a bit like the sentence by Georges Bernanos that Bresson keeps in the Diary of a country priest, it doesn’t occur to me.... I think it’s like that, cinema is a bit like Ventura in the film, who tries to atone and make amends for the faults of all his fellow Cape Verdeans. He tries to pay the supermarket bills, debts, coffins and all the funerals. He tries to pay for everything without a penny, his hands are empty and naked. I think this is what happens today: you try to offer what you don’t have through the cinema. I have very little to give to these people, I can’t pay their fees. They are just like Ventura, I can’t pay them properly, I can’t offer them anything special, no hope for the future. I think that the work we have done together, our collaboration through cinema, with cinema, for cinema, perhaps has allowed me to realise what I wanted, which is to try to put the truth back in its place. They live their life in lies and misfortune. Cinema can dignify life a bit. That’s what it is.

Being there and having been there, the experience of the post-colonial and contemporary reality. How does your cinema evoke life through the passage of time? Is it possible to consider it as a dream experience?

Well, that’s a very complex question! (laughs). I don’t know, I think I’ve already told you something about that subject. I mentioned Wang Bing’s cinema, which is very different from mine, apparently related to documentary, a cinema, I would say, much more direct. And yet, I think that sometimes we achieve the same results, a slightly dreamlike state, in which realism and reality of things are both concrete and indefinite. In Vitalina Varela, for example, there are a series of signals, signs, or clues, almost traces, like in a detective film, in a noir of the 40s or 50s. There are many mysteries, little dark facts that accumulate in this sort of nightmare atmosphere. This reminds me of the rounds Ventura makes as he touches the wooden electric poles... signs, almost like crosses. Symbols of the unknown or signs of death, or indications of facts... In other words, the story of these people, I am not only referring to the Cape Verdeans living in Lisbon, is still to be told, both in Portugal and outside of here. The conditions - you can call them post-colonial realities - of these people, or of these communities living in Portugal, are still to be written. What has been said so far is not appreciable. In cinema, the anthropological or psychological essay has dominated the scene, treating these issues superficially and in the wrong way. Same happened with the television documentary, which is normally very ideologically engaged. I think it is necessary to maintain a certain distance. I think Vitalina manages to maintain this distance because she is a woman. Women respect distance more than men. During the film, Vitalina constantly criticizes what I have said so far, she criticizes this story through her very ancient word. It is a word of suffering and intimacy. Intimacy is always established with those who are absent or with those who have been absent in the past. I think intimacy is political, more and more. Intimacy... yes... how did I manage to establish this intimacy so profound? My difficulty in making films is to keep the intimacy pure in the people I film. I want it to remain secret, that it can be discovered by the viewer without being violated. Do you understand?

Vitalina Varela is a film that seeks light, it really needs it in order to see. What is the relationship between light and memory in your cinema? Is it possible to illuminate oblivion (even that of death)?

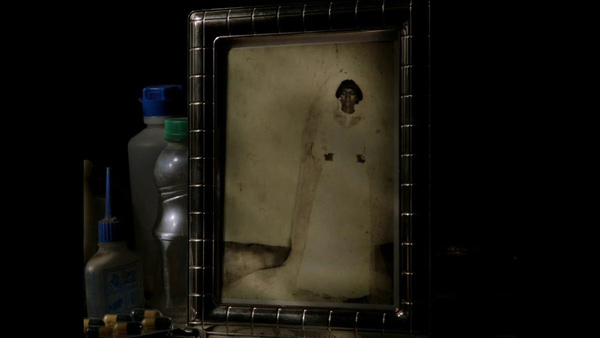

I’ll deal with this in a general way, I don’t know if I can... But your question is related to this film and maybe it’s easier to answer it. Only now, when the film is finished, I think how difficult and tiring the process of making a film is. We are a team of four people, we have worked for a year and a half, so, as I often say joking a bit: "I don’t have time to think about the film shooting it, I have to do it, every day". The routine pervades the work. There is no pre-established theory about light, about nothing. There is something we do doing it, an industriousness. And yet, now I fully understand what happened to our team. We were all facing, and at the same time, a mourning process. We offered Vitalina the possibility to elaborate, through cinema, her mourning. In reality, Vitalina arrived late at her husband’s funeral. She did not see the coffin, the body, did not attend any funeral ceremony. This film allowed her to celebrate all these ceremonies. The small altar with the candles and photographs was set up for the film and remained there until the end of the filming in Vitalina’s house. We could film in the kitchen, in the room, or in another space, even in the street...and this altar was always there. It was the altar prepared for the film and Vitalina. It was arranged for the film, but at the same time, it was not for the film, you know? We strongly felt that the cinema was... that this film was performing a ritual, or a ceremony, if you prefer, for her. Vitalina took advantage of cinema, of our collaboration, to feel, to realize this ritual. Being a ritual of mourning, and a ritual of cinema, we could say, metaphorically speaking, that the light was ghostly. It was a night light, based on two completely opposite poles, it was, I would say, the light of darkness. However, it was also a light of conciliation, calm, something like a cure. The ending needs that visual shock of the daytime sky, with a lot of... The feelings are very different, but it’s interesting your reference to the sky and its light, to the fact that you have caught it as a sign of hope, or peace. It’s curious, you talk about the sky at the end of the film, but don’t notice that this sky is above the cemetery (laughs), the cemetery is above the gravestones, and it’s not bad... Maybe this mourning has been lived for a long time, that’s how it is... Vitalina started to take away the mourning, she stops to dress in black little by little during a year and a half, exactly the time taken to shoot the film. She first removed her skirt and wore a blue handkerchief. He reacted during the film, slowly, to the funeral ceremonies... and we too... the light had these two very extreme sides. The light walks with her, by her side, is part of her anger, her feelings, memories... there are these two faces, it’s always been like that...

Your cinema fights, from the beginning, with death and love, it has always been a long dark night, but in Vitalina Varela you seem to introduce a new theme, the theme of faih. Vitalina herself seems like a priestess, the slow way she walks (always barefoot, as the Cape Verdeans women use), her calm, all this things give her solemnity. Vitalina brings light, illuminates the whole film, relieves the shadows. She is a woman of an intensity that takes your breath away. You left her alone in front of the camera for a long time, but on the other hand, you have said many times that when you film badly a woman films badly everything. It is very beautiful to think about this and it is also admirable to see how you have remained faithful to this: knowledge, both in cinema and in life, with all its mysteries, always passes through women. This is something you have in common with Paulo Rocha. Can we talk about Vitalina as a cathartic figure?

Yes, yes... maybe this is not really a question, rather a comment... (laughs), very right. I don’t know what to say, I agree... I don’t want to take a radical cinephile’s attitude, or necessarily find references, but I see many sisters of Vitalina in the history of cinema. We haven’t tried to imitate anyone, nor have done direct references, but it’s natural that this is the case. I remember when I was young I said that cinema is a relatively heterosexual art (laughs). This statement is a bit controversial, especially nowadays. One only has to think about how many really important things have been done in cinema with women, and for women. Lately I’ve started thinking that Vitalina has many sisters, perhaps the largest number of twin sisters, but in Eastern cinema. You’re right, it perfectly matches Paulo Rocha’s cinema. The fact that you mentioned the bare feet, the hieratic nature of Vitalina, her imposing figure, her silences... I think she has many sisters, especially in the films of Mizoguchi, Ozu, and Naruse. There’s a lot of Naruse, despite the fact that the women in his films are very contemporary, as it were, while Vitalina has a timeless look. Perhaps she oscillates between the martyrs sacrificed in the Middle Ages by Mizoguchi and the contemporary women in Naruse’s Tokyo bars. This element also brings her closer to Paulo Rocha, yes...yes… this is it... (laughs).

What is your relationship with space (starting with No Quarto da Vanda and Juventude em Marcha)? In what terms does the space (like in Fontaínhas's case), and its connection with memory, define the film’s coordinates?

Maybe...so far, I repeat, so far, I don’t know... As Fernando Pessoa said: “I know not what the future will bring”. It is the last sentence written by Pessoa in the language in which he was educated, English (author’s note: actually is: “I know not what tomorrow will bring”). I believe that in this film space can become time. It’s a complicated ambition. Any serious filmmaker tries to make this a reality, to make space become time. Through his culture, his poems, his experiences, the structure and construction of his film, the director will make sure that time can be consolidated or that a special time, different from time, can be revealed. Something very special, that is totally different from our time, from our time... (sighs) ... in which we live badly, especially this one, the time in which we live today, a time without the time to process a thought, right? Our time is a super reactionary time... Nietzsche... even more so in the cinema that despises time. I believe that the ghost that wanders in those streets, alleys and little streets, as well as the shadows in Vitalina’s house, the shadows on the walls, Vitalina’s walking in her house, the walking of those ghosts, of those lost, troubled men, figures that cannot be distinguished: everything moves in a dead space. A space that Vitalina does not know, a space that has just, indeed, no adherence to reality, to truth, is a dead space. I have tried to concretize all this, to give an image to this feeling. Maybe I was able to express a special time, the time of these...it’s difficult to explain...a very special time that is time, I don’t want to say about mourning, I want to say something else, it’s a time in which you don’t just have to say goodbye to something.... I mean, all this is deeply connected to a kind of nature...I admit it costs me a bit to use these terms, but it’s ok! There’s a certain ontology to cinema. Every time we film we’re filming something that will vanish, or has already vanished, that’s it!. Filming the single moment that passes because it fades away. The example of this community, of these people (sighs) has something tragic about it... a brotherhood is established between them, they are almost condemned, indeed, condemned from birth! Their children are equally condemned to the same purgatory or the same unhappiness, or the same exploitation, if you know what I mean. They are people who lose everything many times a day, they are people, as Ventura says: “I don’t want money, I would rather not have one person die a day”. Everything they touch is cursed, even the houses they built in Lisbon, or in the rest of the world, are destined to be demolished, every trace of them is erased. It’s a very strong blow. I think I have already made a film that goes in this direction, which is Juventude em Marcha, in which there is the passage from one space to another, from a space of one’s own, built with everyone’s hands, with their own hands, to a cold, unwelcome space built by foreign hands. Perhaps this last film represents a point of arrival, it is a film that (sighs) ... I would say that it is Vitalina and her apparition, her arrival, her visitation, it is she who brings the memory, so to speak, primordial. That’s why I thought of ending the film in this way. I wanted to go back far, as far as possible, back to the beginning, back to a possibility, to the origin, to the first stone, to the construction of a house, to the construction of a love, to the construction of a life, to the construction of memory. I preferred all this, rather than leaving her segregated, leaving her in the darkness of her house, continuing to live in her memory of death, would have been too easy, too stupid, in fact. Vitalina comes to give this community a chance, let’s say, a chance of memory. I would like that to emerge from the film, whether it was one of the ideas, or one of the feelings. There is something in the film that is about to explode, and it is Vitalina who offers this opportunity...

This is strong. Your work has no aesthetic filiation in Portuguese cinema, but it is very clear that two filmmakers were very important to you: António Reis and Paulo Rocha. Many times you have said that if you make films today it’s because of António Reis. I always thought that Mudar de Vida composes a diptych with Casa de Lava. Rocha describes the forced absence of Adelino, who is in the African colonies to do his military service, and his desire to escape to France; you talk about Leão’s forced absence from Cape Verde, an absence which depends on the need to find a job in Lisbon, and Mariana’s desire to escape from Portugal to Cape Verde. The object of distance changes, but there is one element in common between you and Rocha: the atmosphere between two worlds that seem to exchange shadows. Adelino no longer has a place in his native land, his encounter with his ex-girlfriend, Júlia, is the encounter with a ghost, he forgets her when he is close, he remembers her when he is far away. It’s the same path of Vitalina, Ventura, and many characters from your cinema.

Yes, yes, in the case of António Reis there has always been... it’s true that I started making films because of António, and above all because of Trás-os-Montes, which is the first film I saw of Reis. Afterwards, I saw all the others, but especially Trás-os-Montes, because it’s a film... for me it’s the most Portuguese film in our filmography and it’s a film in which we don’t speak Portuguese, but those dialects that gave rise to Portuguese. We speak a little bit of Galician-Portuguese, which is a northern language and is also spoken a lot in Spain, in Galicia, or Miranda, very local dialects, village dialects (he says it in Italian: dialetti di villaggio). Perhaps it is precisely this aspect that has impressed, encouraged me. This cinema is so far from the city, it’s a village cinema, you know? How did you manage to film so intensely these little myths, these daily gestures that coincide with a past, an ancestral dimension. This language so forgotten, but so original... this was an aspect... today I find it funny, because... I don’t know... just yesterday I witnessed a debate on Vitalina Varela at the cinema. I went into the theatre almost at the end of the film and I suddenly realised that the film was subtitled in Portuguese (laughs). I was shocked! I’ve actually been making films that are subtitled in Portuguese in my country for years! In other words, our condition has changed, Portugal has changed, for a long time now, there is another language, other realities come between us, they surround us, and this change also exists within us, more and more... As for Paulo... yes, it’s true what you said. I had a very strong bond with Rocha. I think Paulo always inspired me to do... Cinema has a very realistic side, it’s obvious, it’s the art of reality, an art of living reality... (sighs)... but it can’t be a glass, it can’t be an electric pole, it can’t be an airplane, it has to be the delirium of a glass, the delirium of an electric pole, the delirium of an airplane, you know? A certain delirium, a distortion is necessary for this reality to be... to be more intense, that’s it! Yes, you’re right, they’re the two filmmakers who accompany me, although I think, more and more, that I have even a certain... very... I mean, a debt to Manoel de Oliveira... sometimes...

We know that you consider Casa de Lava, and certainly all your other films, against O Sangue. We confess that when we came back from Locarno, we read again some interviews related to your first feature film, conversations dating back to 1990/1991. It was moving because you already had very clear ideas and we believe that O Sangue already contains some elements of the cinema that you will make later. It is a film about the memory of cinema, it’s true, but it is also a film about love. Your cinema reflects a lot on love, the only possible subject, in your opinion, in cinema. The fear of love, the fear that people have of getting lost, of making someone feel bad, the fear of waiting, of running away and finally being able to accept love.

I have nothing to say! (laughs) You’ve already said it all... you express yourselves much better than I do... I don’t have anything to say! nothing to add (laughs)...