"If I think about the future of cinema as art, I shiver" (Y. Ozu, 1959)

NAKED LUNCH (5) - The Card Counter + The Master Gardener (Paul Schrader)

Saturday, 11 March 2023 00:24Giona A. Nazzaro

THE LAST THINGS BEFORE THE LAST (1) - Siberia (Interview with Abel Ferrara)

Sunday, 07 June 2020 12:40

Lorenzo Esposito, Giona A. Nazzaro

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (5) - Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino)

Monday, 03 February 2020 20:58Giona A. Nazzaro

CINEMA PSYCHODRAME (6) - Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, Rodney Rothman)

Sunday, 28 April 2019 10:23Giona A. Nazzaro

Climax (Gaspar Noé)

Thursday, 06 December 2018 01:42A bad acid trip gone awry

Giona A. Nazzaro

You have to hand it to Gaspar Noé: he sure knows how to catch the viewer off guard. As much as you may dislike him, Noé always finds a new way for you to hate him. All this obviously looks like a perfectly oiled self-promotion engine that works brilliantly, especially in the festival circuit and in the programmers' outback. The director himself came up with a brilliant press release in which he mocked critics about their dislike for his work (the short version for it is basically, “Now try this!”). But what looked like a brazen act of bravado is actually, if you pay closer attention, a request for a conversation that is yet to be had on his work. Because if you shed away all the gimmicks and effects that create the white noise which is the stuff people talk and write about when they think of Noé, what you are left with are still images. Sometimes, quite unique images that conceal rather interesting films. Let’s put it this way: what if Gaspar Noé was the equivalent (with all the shades of obvious differences in-between...) of William Castle in the European art-house auteur-driven cinema? Castle knew how to get some serious kicks out of his audience and promote himself as a patented and trustworthy “shlockmeister”; “tingling” them to get jolts and chills worth their money. Noé evidently dreams of being an important auteur with a capital A. He grew up devouring tons of films, the “good” ones with the “bad” ones; he craves recognition even though he might pretend otherwise. On the other hand, he simply cannot resist a “good” trick. He loves to play with cinema. He has this carnival side to him that comes directly from the cheaper and sleazier B-movies he adored on VHS (some of the same ones he tributes with an irritatingly sincere homage in the opening of Climax). Sometimes it works (depending on your taste...), sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes, you just get glued to the screen even though you can’t help thinking something has gone completely wrong while at the same time you reluctantly admire his childlike arrogance that gets its claws in you through sheer willpower. Climax works like this. It (seems to) offer(s) itself like a reflection on the French state of the union in the wake of the Bataclan massacre proudly declaring its Frenchness (like a long delayed nod to the expired “French touch” in house music...) and thus immediately injecting the viewer with the suspicion “Is this the way self-styled cool auteurs have gone Macron?”. But you need to hang on. A fierce and frenzied choreography, filmed in one breathtaking take, unfolds for what seems to be an eternity... and then it goes on and on. But some cracks begin to appear... while the long take goes on. The perfectly-knit unity of the dance ensemble falls apart while the film gets tighter and tighter. A thought begins to loom: could this be Noé’s take on Argento’s Suspiria? All the clues are there: a dance academy, a mastermind that drives everyone else crazy, a huis clos, the overbearing presence of pulsating music. Climax is Gaspar Noé literally taking his cinema into the void. Relentless and brutal, yet exhilaratingly intoxicating, he literally raises a hymn to the yet unseen possibilities of cinema. The physicality of it all is the perfect reminder that cinema is still something that you craft. Bodies, lights, movement, angles: all these elements come together in Noé’s Climax in a declaration of love: this is how we still make cinema. The slightly disquieting authoritarian stance of Irreversible is gone, but Climax is no less discomforting. You can feel that the architect twirling above has let go of his grip on the viewer’s eyes (it already happened with Love) but the outcome isn’t bleak any lesser. Cinema is no longer a collective dream (or project...) but a bad acid trip gone awry. Climax is the film showing how France (and the rest of Europe and the world as well...) rips herself apart. It’s ugly, violent, but weirdly fascinating as well. Noé’s long take feels like a documentary observational strategy. An exercise in entropy. As if cinema were really the very last element trying to keep it all together... but it is obviously bound to fail. Noé’s sardonic and bitter grin suggests that his film should have been branded anti-Climax... “not with a bang, but a whimper”. And, for once, even though some hints were already available in Enter the Void and Love, Noé really seems to care. Which is good news.

Black Panther (Ryan Coogler)

Saturday, 05 May 2018 08:56(Or why I didn’t get

Black Panther the first time around…)

Giona A. Nazzaro

Well, who doesn’t like the mighty T’Challa, the wise monarch of Wakanda, and the first African-American superhero in the Marvel Pantheon? You do not need to be a comic-book nerd to have heard about him. His iconic image has spread across all the realms of pop culture and cultural studies alike. Suffice to say that T’Challa is a real superhero, because he’s made of and completely relates to the African-American experience; its contradictions, the still unsolved social rights issues, and its painful historical complexities and atrocities. For some (those who usually do not think that Black Lives Matter…), Black Panther might even be a tad too close to home for comfort. Therefore, also this side of the pond there were many, many expectations about Coogler’s take on Black Panther. Since with his previous work Creed he managed to restore Rocky’s working-class roots, and thus partially return the boxer’s story to the African-American community (Apollo is Rocky’s spiritual father and mentor, something that those who were eager to write off Stallone forgot too easily and too quickly…), there was genuine curiosity about how he would tackle T’Challa’s bourgeois and political contradictions. A monarch, a rebel, a scientist, a millionaire, a reformist who boasts revolutionary credentials (this is why, later on, Marvel needed Luke Cage, hero for hire…). Obviously, there also was a monumental promotional job involved before the release of Black Panther. Not a day went by before the film hit the theatres without some major trade featuring an article about Coogler’s upcoming movie. And yes, there were also the messianic tones rising from the African-American community hailing it weeks before its release as a political, cultural, economic gamechanger. Therefore, when the film was finally on the big screen, a certain degree of disappointment was felt this side of the pond, at least by yours truly, an unabashed fan of the MCU (yes: guilty as charged). Some of us over here did not dare to admit it openly - you do not want to be in the same league with Trump and his ludicrous circus of freaks - but it felt as if the much-heralded celebration of the African-American experience had been transformed in a Disneyland theme park (and after all, Disney owns the MCU…). (The French magazine “Positif” brushed it off exactly in those terms a bit later). Somehow, we felt let down, to the point that even the set pieces felt lacklustre (they are not, of course, not worse than Ant-Man, anyway…). By the way, let’s not forget that, when the Saudis decided to finally lift their ban on cinema, they decided that Black Panther should be the forerunner in their domestic theatres. So, what went wrong with some experiences of the first (obviously European, white, left-wing, etc….) viewing of Black Panther? Simply put, everyone (and their mother…) has their own take on what the African-American experience should be (especially the white guys, especially if European, those that would have voted for Obama the third time…). And this goes a long way in explaining how even the best intentions (especially those…) can go wrong. Ok: you went in the theatre thinking, due to your white privilege, of Amiri Baraka, Max Roach’s We Insist! and Melvin Van Peebles. But what you got was an incredibly tight, sleek P. Daddy tune as if rewritten by Kendrick for Rihanna. Of course, you are caught off guard (wait: are they re-assessing also the legacy of the “other” Panthers as well…?). But it’s only your (our…) fault. Entrepreneurs such a Jay Z. should have taught us that, in a Marxian way, you need to become the master of your own means of productions. Once you do that, you can also effectively control your own image. Black Panther does exactly that. Because form is content. It offers a hypertextual image of the African-American experience that can be easily shared (sampled…) and therefore transmitted as a mythopoeic lemma. That’s exactly why Black Panther is really a ground-breaking and game-changing film. It finally breaks down the cultural barriers between the so called high- and low-brow definitions of African-American experience and culture and manages to create a new standing ground that is larger and complex. Its boundaries extend from the fandom of comic-books to action figures and from hip-hop to pan-African consciousness. The scope of what Black Panther attempts and succeeds to do is so broad that it could fill a Kamasi Washington suite. And there would still be some room left to fill. It basically says that Alice Coltrane and T’Challa belong in the same world because both are expressions of the African diaspora. And that our picture of what “Africa(n)” is needs a complete rethinking. Time’s up. The African-American experience needs to be finally considered as a whole again and not as isolated segments to be used only for academic dissertations. And if this means that Black Panther becomes one of the most gigantic blockbusters in the recent history of Hollywood’s box office smash hits, so be it. There’s still a lot to be done, but this simple and extraordinary fact might finally be a step in the right direction (and maybe it will finally dawn on us too, on the other side of the pond). After all, as Idris Ackamoor would claim, aren’t we all Africans?

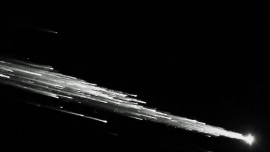

Meteors (Gürcan Keltek)

Monday, 27 November 2017 10:20Giona A. Nazzaro

The thing itself

Gürcan Keltek’s first feature-length film is an astonishing survey of the possibilities still open and available to those who are working inside the boundaries of cinema. Tackling images and cinema as tools and means to further inquire about the set of rules that film-making is still dealing with, Keltek creates a tremendous visual and sensorial experience that has no equals in contemporary cinema today (with the only exception of Ala Eddine Slim’s work). His visual approach, already clearly refined and fully fleshed out in Fazlamesai (Overtime) – his first short film – evolves further on in Meteorlar (Meteors). Structured in what appears to be a narrative loosely tied by several chapters, there is a deeply resonant web of cosmic audio-visual fabrications. It deals obviously with the Kurdish identity and war, but the film also manages to evoke the so-called documentary elements of a broader context. The film begins and ends with a moon that slowly rises in the night sky. And it is the very same moon that ends it. Inbetween, there are scenes from a mountain hunt, the Kurdish guerrilla, and violent protests against the Turkish military and police as well as the voices of children and an unbelievably breath-taking meteor shower. Thus, Keltek manages to do several things in just one film. He questions the very notions of documentary and militant and politically engaged film-making. Keltek, an extraordinarily accomplished visual film-maker, depicts not only a very specific region (the southeast of Turkey), but produces a consistent mythopoeic universe in which image and sound redefine both the notion of watching and that of the image.

Shot in an elegant, grainy, very low-defined black and white, the image seems to be always on the verge of tearing itself apart of to simply expose its pixels (and it does happen…). Keltek tests the texture of the image as the image itself were a war zone. It is as if Keltek needed to go to war against the image to try re-thinking the possibilities of how to film a war in the current context. So, the unthinkable happens: the film becomes an immense and pulsating cosmic canvas, as if Tangerine Dream where reprocessed by Aphex Twin’s deconstructing approach. This is how Keltek can call upon an entire country and its politics in a precise historical moment and in a brutally, excruciatingly exact way.

Thus, Meteors becomes Turkey itself. No longer a film “about something” but the “thing” itself. Keltek’s keen ability for filming and framing landscapes, volumes, depths, texture and the dialectics of sound and vision, reaches its peak at the sight of Nemrut’s head. Suddenly, we are no longer on the northern border of the Kurdish district but in a completely different time and place. While the grainy images never allow us to forget that we are watching someone who is working (making a film…), the sheer volume of conflicting elements allows Meteors to transcend its own limits. The film becomes a powerful rumination on mankind and the void they are living in, but also a reflection of the endless returning cycle of the seasons of war and grieving.

Out of nowhere though, two snakes dance their mating rituals. It’s a mesmerizing and disturbing image. We cannot tell the two snakes apart.

Gürcan Keltek creates a sensuous and mysterious place of cinematic (im)purity. By accepting in the fabric of his film all those elements that are usually shunned upon, he also questions the notion of economic politics in film-making. Meteors is a new territory on the maps of contemporary cinema. It’s a filmic abstraction that becomes the most accurate depiction of what can still be done with cinema today. A timely and much needed reminder of the necessity of re-thinking the overall context of contemporary filmmaking.

Meteors is already a modern-day classic. A film on which we will look back whenever we will need tools and ideas and images, whenever we need to redefine and re-orient our position.

It’s that rare and precious film.

LOTTE IN ITALIA (2) - Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino)

Thursday, 20 July 2017 09:25Giona A. Nazzaro

THE SUPERHERO OF THE SPECIES - Dr. Strange (Scott Derrickson)

Thursday, 30 March 2017 08:06Giona A. Nazzaro

MASTERS - Brooks, Meadows and Lovely Faces (Yousry Nasrallah)

Saturday, 19 November 2016 14:33Giona A. Nazzaro

Ultimi articoli pubblicati

- 2025-03-24 Chime/Cloud/Serpent’s Path (Kurosawa Kiyoshi)

- 2025-03-24 Abiding Nowhere (Tsai Ming-liang)

- 2025-03-24 The Box Man (Gakuryū Ishii)

- 2025-03-24 Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)