"If I think about the future of cinema as art, I shiver" (Y. Ozu, 1959)

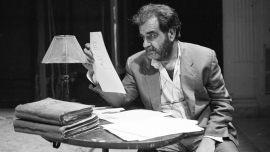

Gli uomini di questa città io non li conosco – Vita e teatro di Franco Scaldati (Franco Maresco)

Tuesday, 27 October 2015 14:32Making someone exist

Boris Nelepo

As the founding father of the Cinico TV, since the early 1990s Franco Maresco has been braiding together a cinematic chronicle of his native Sicily and, above all, hometown of Palermo, performing for his homeland the same duty documentarian Peter von Bagh served to Finland, or Želimir Žilnik to the former Yugoslavia and Serbia. This kind of history couldn’t be written without appeals to certain exemplary individuals, so Maresco’s latest, Gli uomini di questa città io non li conosco – Vita e teatro di Franco Scaldati, bears a dedication to Franco Scaldati, the grim theater director and playwright, "the Beckett of Palermo" who once reformed the language spoken on stage as he smuggled in the Palermo dialect along with the local color.

Scaldati’s body of work represents an act of relentless resistance both to the political degradation of his country and to the intellectuals’ comfortable partisanship. In the late 1970s, at the peak of political turbulence, he abandoned the social radicalism of his early plays for the pure poetry of Lucio, a tale of a naive philosopher who converses with the moon, which alienated from him the communist sympathies. Tired of being broke for years, neglected by cultural institutions, and relegated to basement venues, Scaldati at last found employment at Palermo’s major theater, Biondo, much to the chagrin of the bourgeois snobs craving a nonconformist poster boy. Be that as it may, there he remained a hired hand, unable to produce his own plays until the late 1980s when he finally managed to launch Il Piccolo Teatro, a company as independent in spirit as it was short-lived. In his later years, Scaldati almost gave up on his vocation and limited his public appearances to recitals of his new works, mostly comprising phonetic games. Perhaps disillusioned with the idealistic view on art’s global mission, he nevertheless continued to engage in direct activism: for over a decade, Scaldati ran an acting lab for at-risk youth. Rather than dream of "making a difference" with his art, or worry over the artistic results, he simply relished the experience of interacting with people who couldn’t fathom a life outside their bad neighborhoods.

I Don't Know Anyone in This Town is an especially personal and intimate project for Franco Maresco, who considered Scaldati, deceased in 2013, a friend, a teacher, and a mentor (last year he even put on a standard-Italian production of Lucio). Scaldati himself dabbled in acting appearing in several movies by the Taviani brothers and Giuseppe Tornatore, but it was Maresco who captured in full his penchant for comedy in The Return of Cagliostro. The principal ambivalence of I Don't Know... lies in the fact that on the surface, it looks like an ordinary documentary, as good as made for TV. One of the most truly singular filmmakers working today, Maresco chose to forego any kind of authorial voice or personal style, so the Venice audiences, by and large, dismissed the festival’s greatest masterpiece as a strictly provincial narrative handled too conventionally. What does it matter, though? After all, Maresco’s Scaldati, whose existence had almost escaped us but didn’t, is a much more compelling character than most fiction has to offer. Making someone exist – isn’t it as ambitious a task as today’s filmmaking can tackle?

Of course, just like Maresco’s masterful Belluscone. Una storia siciliana released last year, I Do’'t Know... tells a story of defeat - an individual’s, a country’s, art’s, Franco Maresco’s own. Only once did Scaldati enter the Biondo Theater through the main doors as his casket was carried inside to the sound of politicians rhapsodizing about "losing the living embodiment of Palermo’s soul." Two years later, Maresco comes to the theater to ask its audience members if they’ve ever heard of Franco Scaldati. No, no one has. However, the film’s epigraph perfectly encapsulates what Scaldati had to say on the subject: “Beauty is of the defeated. The future is not of winners, it is of those who are able to live”.

Cemetery of Splendour (Apitchapong Weerasethakul)

Sunday, 19 July 2015 10:10Between dream and nightmare

Boris Nelepo

Hobbling nurse Jen without delay singles out a sleeping soldier who looks just like Clark Kent, Superman's alter ego. His superpower is being able to smell the flowers he sees in his dreams - some skill for a military man. If it were up to him, Itt the soldier would rather sell mooncakes than wash the generals' cars. But, what is a Thai filmmaker to do when last year's coup, his country's twelfth in 80 years, leaves him petrified with fear and despondency? Apichatpong Weerasethakul doesn't want to show weapons or bloodshed or suffering on screen; nor does he know how. Though an articulate political statement, his Cemetery of Splendour also relates a tale of impossible love reminiscent of Jean-Claude Brisseau's The Girl from Nowhere, weaving a dream chronicle into a childhood memoir.

Here director revisits his hometown of Khon Kaen, for which he longed in Chicago while working on his short 011664322509 and where the autobiographical Syndromes and a Century was partially set. The visionary auteur often uses the expression “the burden of memory”. On his journey northeast, he circles around the locations of Uncle Boonmee..., whose characters referred to some "brutal hunt for communists." In Blissfully Yours, a character points to the jungle and says, "This is where the ghosts of Japanese soldiers dwell." The goddesses in Cemetery tell Jen outright that the earth beneath her feet is strewn with corpses.

The past holds people hostage. A portrait of General Sarit Thanarat, who was instrumental in the 1947 coup and staged the insurgences of 1957-58, now oversees the soldiers in the canteen. As it pans across town Apichatpong’s camera comes to a halt at a militarist low relief also dedicated to Thanarat. Unlike Joe's earlier vistas of mellow moods, Cemetery of Splendour appears shot through with currents of anxiety, disquiet, and paranoia. In one of the film's recognizable leitmotifs, the characters treat each other with continual mistrust, suspecting some clandestine identity in everyone: is he a terrorist, police spy, FBI agent? Jen suddenly remembers that her ex-husband was in the army, too - and a veritable monster he was. His name turns out to be Colonel Narong. A biographical detail from the actress's life, but at the same time Colonel Narong, a member of the “Three Tyrants” that seized the power in the 1960s, did exist. “When you’re asleep your metabolism slows down. Someday you’ll see a better future,” Jen promises Itt.

A dissolve - an image from one scene transitioning slowly into the next - is perhaps the most apt word to describe Cemetery. A former school is transformed, temporarily, into a hospital. In the movie’s climax, Keng the medium channels the spirit of Itt who lies asleep and thus evidently suggests a metaphor for the acting profession, even though the audience for this performance consists of Jen alone. It’s worth noting that the part of Itt went to the same actor who had played soldier Keng in Tropical Malady, so the medium in the new movie quite literally becomes the old Keng. When in the medium’s body, Itt takes Jen for a walk through the woods showing her an imaginary reality that includes a king’s throne room, a music room, a room of mirrors, and pink marble. The dissolve technique is deployed to great effect in the giddy scene at a movie theater, where Apichatpong captures in an uninterrupted take five escalators moving in different directions; slowly, the images of soldiers dozing in a hospital seep through onto the screen. The ward we see now is equipped with bizarre, downright fantastic tubes constantly changing color.

This color therapy is supposed to chase away nightmares. Jen professes her love for Itt as she only knows how: “When you’re asleep even the bright city lights look boring.” At some point Jen wants to wake up, and Itt instructs her to open her eyes as wide as she can. In the very last - and most disquieting - shot, she sits in front of a furrowed football field, children playing among holes, and tries her best to open her eyes. However, the hardest part is to draw the line between a dream and a nightmare.

Ultimi articoli pubblicati

- 2025-03-24 Chime/Cloud/Serpent’s Path (Kurosawa Kiyoshi)

- 2025-03-24 Abiding Nowhere (Tsai Ming-liang)

- 2025-03-24 The Box Man (Gakuryū Ishii)

- 2025-03-24 Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)