"If I think about the future of cinema as art, I shiver" (Y. Ozu, 1959)

Nato a Roma nel 1968 si occupa di bla, bla, bla. Collabora con Skillweb, Lynx e altre società nel campo delle nuove tecnologie di comunicazione.

Appassionato di fotografia, montagna, ecologia e libertà, ASR, subbuteo e bicicletta, grafico e webmaster spesso per lavoro, spesso per piacere.

Tra le sue opere più importanti

- bla bla bla

- bla bla

- bla bla bla bla

D. A. PENNEBAKER

Yorgos Tsourgiannis

D.A Pennebaker often spoke of Powell & Pressburger’s “I know where I’m going!” as his favourite film in the world. Many others have loved it; Linklater, Hegedus, Scorsese, Chandler, Rivers. Novelist James Agee, responsible for “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men”, a literary masterpiece and chills-producing specimen of deeply evocative, affecting and ripe with dignity observation on human life, yet not one to mince his words when it came to film criticism, praised IKWIG describing it as an “unobtrusively remarkable study of a place and its people” in his 1947 review of the film. Sensitive misty photography, ingenious use of both sound and music, lively and fleshy dialogue coming out the mouths of nuanced characters and stunning performances are matched by the inherent openness and curiosity of the filmmakers. The result is an astutely authentic evocation of place and its effect on people. Plenty documentary like instances of the Hebrides life and folklore are offered; the céilidh dance, the seals’ singing, the Gaelic banter, the locals’ gossip or the Corryvreckan maelstrom legend.

Yet this is not why Pennebaker absolutely loved this film to the point of wanting to “hug it somehow!” He marvelled instead at how fantasy is balanced with realistic scenes, how for instance real Scots are incorporated into the story and at how Powell dealt with the reality of what he found there. “…he (Powell) was turned loose in a place that he kind of knew about, but didn’t know—and that, to me, kind of speaks to the future somehow….I’m sure that all of the good dramatists that have ever lived have thought of that… hundreds of years later. Can it still work? All those people in my head, can they come out and live for somebody else? This is what woke me up!”

This quote in some way epitomises Mr Pennebaker’s philosophy and the creative process behind a lifetime drenched in film.

Sort of like taking the dog out for a walk, never quite knowing what exactly will happen. Scavenging for camera worthy, theatre important, “interesting” moments and gambling on his sometimes ordinary, sometimes extraordinary subjects performing themselves and gambling on himself dancing around them with his camera, performing with them to somehow capture the real. In a language that speaks to the future. But not with a lot of words.

Ever since that 3rd Avenue elevated train departed for one of its numbered journeys in Manhattan, D.A Pennebaker on board with Duke Ellington from the loudspeaker has graced us, (for the most part together with his creative partner Chris Hegedus) with a multitude of such moments.

Say,

his three year old daughter strolling on central park, Diane Arbus at the back of a car on the way to Timothy Leary’s marrying to Ms Schlebrugge, Uma Thurman’s mom, Tom Moore casually discussing Feydeau farce on the ride back from the airport. Carol Burnett’s class act in keeping a Broadway audience aroar with laughter whilst backstage repairs are underway. A bare-chested Dave Gahan singing over a flipper or later reflecting on his killing impulses because of pent up stress. Germain Greer’s eye-rolls to a patronising Norman Mailer or Susan Sontag calling him out for his misinformed gallantry. George Stephanopoulos trying to trim half a second, maybe a whole second off Bill Clinton’s speech. Clinton calling Hillary his “Valentine’s Day girl”. Producer Rocco Landesman wondering on camera if his director was the one to be split in half. Chef Pfeiffer discussing the fou fou of creampuffs or an embarrassed Regis Lazard lamenting the breaking of his almond cookies in front of his bemused wife. Ziggy singing “Time takes a cigarette…” at the Hammersmith or Allen Ginsberg skulking around as Dylan flips cards.

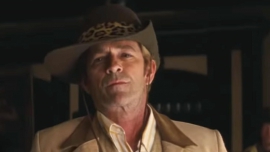

LUKE PERRY

Simone Emiliani

Luke Perry torna a vivere nel breve tempo di una scena di C’era una volta a…Hollywood, l’ultimo film di Quentin Tarantino. Nella versione in dvd in uscita proprio in questi giorni negli Usa, ci saranno 20 minuti in più che mostrano altre scene della serie western Lancer in cui Rick Dalton/Leonardo Di Caprio è la guest star. In uno di questi frammenti recuperati, Perry che interpreta Wayne Maunder, è vestito di azzurro, ha il bastone e cappello, cammina zoppicando e litiga con James Stacy/Timothy Olyphant che di quella serie è stato il protagonista ‘buono’. L’ennesimo tentativo, estremo e grandioso, di una possibile inversione di una carriera. Sempre irrimediabilmente legata alla figura di Dylan McKay di Beverly Hills 90210. Che oggi invece non solo è un magnifico reperto, ma rappresenta quella commedia sentimentale che nel cinema/tv statunitense sembra definitivamente scomparso. Non solo come forma narrativa, ma proprio come corpo. C’è un episodio della prima stagione, Una storia romantica. Brenda e Dylan hanno litigato. Si sono poi chiariti e si baciano appassionatamente sul divano. Quei fasci di luce anni ’80 magici. Tra Ridley Scott e Adrian Lyne. Quel cinema videoclip che si è spostato sulla tv anni ’90. Dove Dylan è forse una delle re/incarnazioni più rappresentative. Che forse non doveva mai uscire da quel ruolo. E da quel programma. E in Italia l’effetto Luke Perry si vede in uno dei migliori cinepanettoni di sempre, Vacanze di Natale ’95 di Neri Parenti. Forse è già un’apparizione dall’aldilà. O un fantasma. Un fascio di luce simile a Beverly Hills 90210. Appare Luke Perry che è Dylan (quasi simbiosi attore/personaggio) sulle note di No More I Love You. Forse è il tempo dell’attesa, del sogno. E quell’immagine è una soggettiva non dichiarata, quella di Cristiana Capotondi adolescente. Così, forse, come lo vedevano, molte coetanee. E il nostro sguardo era inevitabilmente filtrato da quello loro. Ci sono molte doppie identità di Luke Perry che il cinema non ha adeguatamente valorizzato. Come quella della sua sterzata, impossibile inversione nello straordinario Normal Life diretto da John McNaughton, feroce come Henry, pioggia di sangue. Un agente di polizia che diventa un rapinatore di banche per sopperire alla sua situazione economica dopo che si è sposato con Pam. Lui e Ashley Judd, una delle coppie potenzialmente più forti e oscurate in un poliziesco che poteva, anche questo, arrivare dal decennio precedente. Forse, davvero, per Luke Perry, bastava essere nato dieci anni prima.

AGNÉS VARDA

Naked

Seize the time, questa frase mi appare ogni volta che sento il tuo nome, Agnés, da quando vidi l’omonimo lavoro di Antonello Branca. Perché nonostante il film del fotografo/filmmaker abruzzese sia più articolato, diretto e approfondito, per tutti è sempre stato il tuo Black Panthers il film sul movimento afroamericano. Afferrare il tempo è stata una tua prerogativa, con tutta la selvaggia bestialità che distanzia l’afferrare dal prender(si) tempo. In questo senso Cléo, con la sua ora e mezza effettiva tra le 5 e le 7, resta lavoro manifesto della tua opera, anche se a differenza di tanti altri autori hai avuto la fortuna rara che in tanti conoscono le tue immagini prima ancora che il tuo nome. Fino alla fine hai cercato il momento giusto in qualsiasi posto, come a voler inchiodare sempre un tempo nello spazio che è il (tuo) cinema, sempre avanti, con quell’annusare l’aria alla ricerca dell’attuale tipico dell’umanità sinistra. È quest’ultima, con cui intessevi una dinamica tra “civetteria e angoscia” (così intitolasti la tua presentazione di Cleo) che vuole impalare il tuo cinema e ne fa bandiera sventolante ai capricci dei venti (Agnés la femminista, Agnés la comunista, Agnés l’artista e così via) anziché lasciarlo libero, spazio nello spazio, inafferrabile come tu sei stata.

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (1) - Vitalina Varela (Interview with Pedro Costa)

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (2) - Dolor y Gloria (Pedro Almodovar)

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (3) - Non c'è nessuna Dark Side (atto uno 2007-2019) (Erik Negro)

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (4) - Liberté (Albert Serra)

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (5) - Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino)

LE TEMPS RETROUVÉ (6) - Heimat Is a Space in Time (Thomas Heise)

SMASH CAPITALISM! - Uncut Gems (Josh & Bennie Safdie)

Ultimi articoli pubblicati

- 2025-03-24 Chime/Cloud/Serpent’s Path (Kurosawa Kiyoshi)

- 2025-03-24 Abiding Nowhere (Tsai Ming-liang)

- 2025-03-24 The Box Man (Gakuryū Ishii)

- 2025-03-24 Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)